No one is ever satisfied with available data to describe the vegetation in their area of interest. There are many very good data sets out there, but I suspect none of them meet every one’s needs with regard to level of community or species detail, accuracy, or scale. As a result, we are always generating new data to describe vegetation, often with a specific need in mind. However, this typically leads to the question:

How does this data set compare with data sets X, Y and Z?

I recently published a paper on a methodology to map forest functional type at the interface with the shrubland ecotone (Assal et al. 2015). I used 10 m SPOT imagery to capture the extent and juxtaposition of the small forest patches found in a matrix of sagebrush shrubland. I compared this local data set with three common regional data sets, but due to space limitations I had to cut this from the manuscript. However, I thought a basic comparison would be of interest to some, so I have posted the comparison below.

METHODS

In order to compare our map with regional data, we reclassified NLCD, LANDFIRE and ReGAP data into deciduous forest, coniferous forest and non-forest (Tables 1-3). We identified contiguous patches of forest cover using the same procedure as above. We calculated basic landscape metrics (total cover area, mean patch size and number of patches) to provide a simple, quantitative assessment of how each product characterized the forest cover of the study area.

Table 1. LANDFIRE reclassification crosswalk table (version LF_1.3.0 (2012) was used in the analysis).

| Map Class | LANDFIRE Existing Vegetation Type Name (EVT Code) |

|---|---|

| Deciduous Forest | Rocky Mountain Aspen Forest and Woodland (2011) |

| Rocky Mountain Gambel Oak-Mixed Montane Shrubland (2107) | |

| Coniferous Forest | Northern Rocky Mountain Subalpine Woodland and Parkland (2046) |

| Rocky Mountain Lodgepole Pine Forest (2050) | |

| Southern Rocky Mountain Dry-Mesic Montane Mixed Conifer Forest and Woodland (2051) | |

| Southern Rocky Mountain Ponderosa Pine Woodland (2054) | |

| Rocky Mountain Subalpine Dry-Mesic Spruce-Fir Forest and Woodland (2055) | |

| Middle Rocky Mountain Montane Douglas-fir Forest and Woodland (2166) | |

| Rocky Mountain Poor-Site Lodgepole Pine Forest (2167) |

Table 2. NLCD reclassification crosswalk table (version NLCD 2011 was used in the analysis).

| Map Class | NLCD Classification Description (Class Value) |

|---|---|

| Deciduous Forest | Deciduous Forest (41) Mixed Forest (43) |

| Coniferous Forest | Evergreen Forest (42) |

Table 3. ReGAP reclassification crosswalk table (version 2 ReGAP data (2011) was used in the analysis).

| Map Class | ReGAP Ecological System Description (Level 3 Code) |

|---|---|

| Deciduous Forest | Rocky Mountain Aspen Forest and Woodland (4111) |

| Coniferous Forest | Inter-Mountain Basins Aspen-Mixed Conifer Forest and Woodland (4324) |

| Northern Rocky Mountain Dry-Mesic Montane Mixed Conifer Forest (4524) | |

| Rocky Mountain Lodgepole Pine Forest (4527) | |

| Southern Rocky Mountain Dry-Mesic Montane Mixed Conifer Forest and Woodland (4528) | |

| Rocky Mountain Subalpine Dry-Mesic Spruce-Fir Forest and Woodland (4531) | |

| Middle Rocky Mountain Montane Douglas-fir Forest and Woodland (4543) | |

| Northern Rocky Mountain Mesic Montane Mixed Conifer Forest (4609) |

RESULTS

The landscape metrics calculated from the regional data sources revealed high levels of disagreement between land cover products. LANDFIRE and ReGAP reported the most total area of deciduous forest with 44.3 km2 and 41.7 km2 respectively (Table 4). However, the LANDFIRE map has over five times the number of patches as the ReGAP map, resulting in a much smaller mean patch size. NLCD has the smallest amount of deciduous forest and the fewest patches. Our synthesis map had the most deciduous patches and the smallest mean patch size, with a total area between the high and low range of regional map products. Conversely, NLCD identifies the most coniferous forest in the study area (Table 4) with a large average patch size (0.073 km2). ReGAP and our map report similar total area (38.8 km2 and 34.4 km2 respectively) of coniferous forest. However, our synthesis map has nearly five times the number of patches and therefore a much smaller mean patch size. LANDFIRE reports far less coniferous forest, yet a high number of patches.

Table A4. Results of the land cover comparison between the synthesis map and regional data products.

| Deciduous Forest | Coniferous Forest | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Total Area (km2) | No. of Patches | Mean Patch Size (km2) | Total Area (km2) | No. of Patches | Mean Patch Size (km2) |

| Synthesis Map | 27.2 | 7110 | 0.004 | 34.5 | 2362 | 0.015 |

| LANDFIRE | 44.3 | 6518 | 0.007 | 13.7 | 2001 | 0.007 |

| NLCD | 15.4 | 812 | 0.019 | 86.7 | 1192 | 0.073 |

| ReGAP | 41.7 | 1223 | 0.034 | 38.8 | 496 | 0.078 |

DISCUSSION

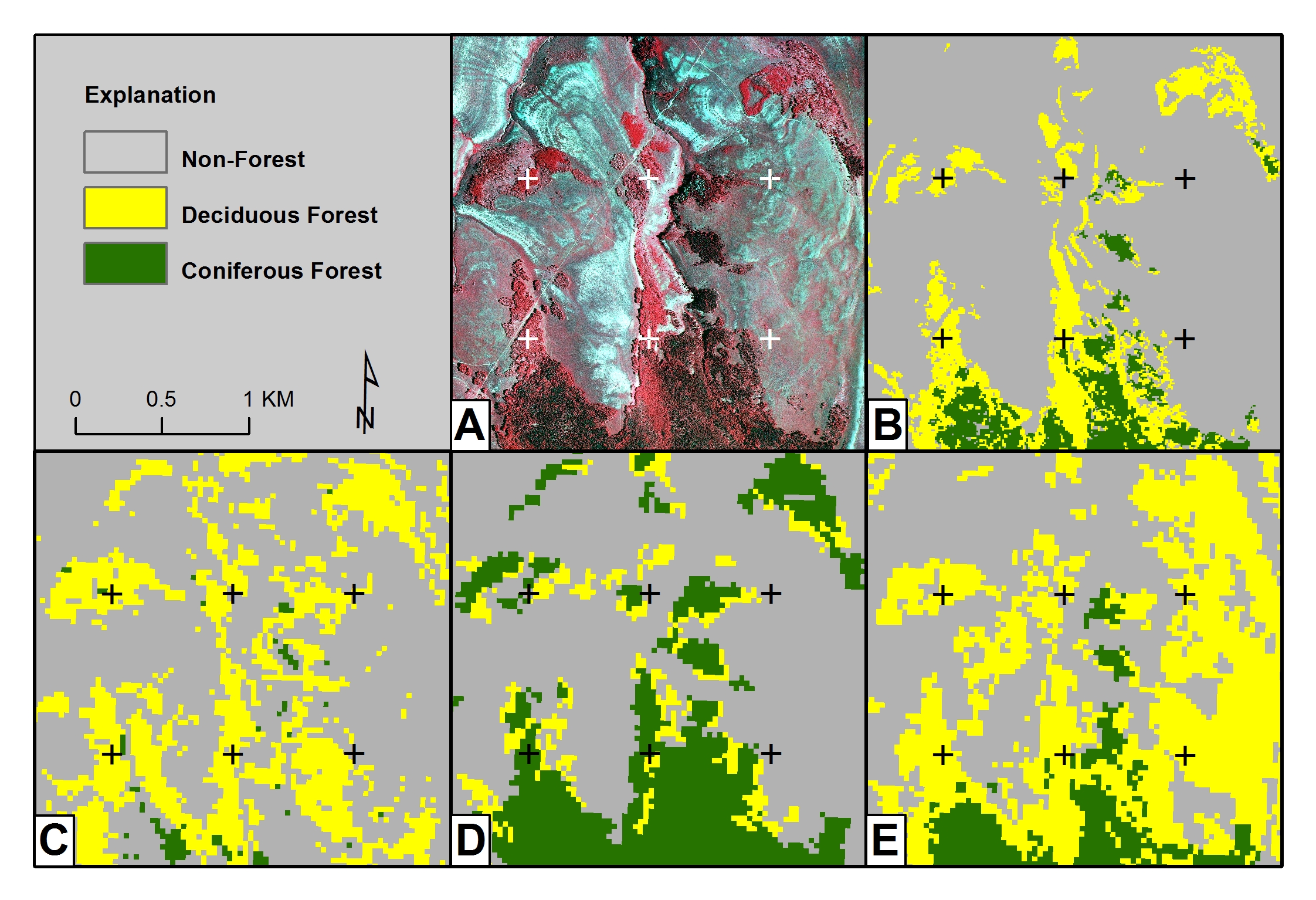

Our results show that fine-scale mapping is necessary to capture the spatial heterogeneity of deciduous and coniferous woodlands characteristic of this ecoregion (Figure 1B). Figure 1 depicts a representative area on Little Mountain which highlights the small size of isolated forest patches of the study area (Figure 1A). The LANDFIRE map overestimates deciduous forest cover and contains many single pixels, inflating the number of patches (Figure 1C). The NLCD map underestimates deciduous forest (Figure 1D), whereas the ReGAP map overestimates deciduous forest at the expense of non-forest (Figure 1E). Native LANDFIRE data classifies significant portions of coniferous forest as shrubland, resulting in lower total area (Table 4, Figure 1C). NLCD reports a large area of coniferous forest, in part because it is the only product that does not differentiate between montane conifer species and less dense conifer woodland at lower elevations (Table 4).

The results of the land cover comparison highlight the differences in land cover data that are currently available at regional scales (Figure 1C-E, Table 4). We acknowledge our comparison is biased since our model utilized finer scale data. It is not our intent to criticize regional land cover data products, rather we identify the differences in localized areas that exhibit high levels of spatial heterogeneity. Regional land cover products were developed with more coarse data (e.g. 30 m Landsat) at much greater spatial extents than our modeling and mapping process. However, in our highly heterogeneous study area, there is little agreement between the land cover data. Our methodology is capable of detecting both total forest cover as well as the landscape juxtaposition of forest patches that are representative of this area (Figure 1B). We conclude that ecological studies requiring highly accurate forest cover and plant functional type should consider using multi-temporal SPOT imagery to derive regionally specific land cover maps.

Much of the information on this post was adapted from Appendix A in Assal 2015.

Literature Cited:

- Assal, T.J. 2015. The ecological legacies of drought, fire, and insect disturbance in western North American forests. Dissertation, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

- Assal, T.J., Anderson, P., Sibold, J., 2015. Mapping forest functional type in a forest-shrubland ecotone using SPOT imagery and predictive habitat distribution modelling. Remote Sensing Letters. 6, 755–764.

Top image: Aspen and Coniferous woodlands, Little Mountain, Wyoming.